Performing for the Camera

Since the late 1960s, artists in Israel, like their peers abroad, began to reject the traditional art object in favor of a more conceptually driven and time-based creation process. Different factors contributed to this shift, among which was the post-1968 embrace of an anti establishment and anti capitalist stance. In Israel, this trend was especially felt following the calamitous Yom Kippur war of 1973 that left the public in a state of trauma and with deep-seated suspicion toward the government, the hegemony and all of its institutions.

A large part of the avant grade activity in Israel began to coalesce around staged actions and performances. This type of art was generally experienced live, but what ensured its enduring life was, above all, the camera. The images that result function as recordings of an event but also as autonomous works of art in the absence of a performing body, such as in works by Efrat Natan and Yocheved Weinfeld. Into the complex network that weaves itself in the early1970s between performance, staged action and photography, another medium was introduced around that time with the early video experimentations by artists like Michael Druks and Buky Schwartz, both of whom were based outside of Israel but had left a lasting imprint on future generations of video practitioners.

By the end of 1990s and into the early aughts, artists — primarily female artists — were increasingly using the camera to test the physical and psychological limits of the body, as can be seen in works by Hila Lulu Lin, Nelly Agassi and Manar Zuabi. Often through grueling or Sisyphean tasks, these artists in different ways linked the disciplining of the female body to sexuality, desire and violence. Artists like Sigalit Landau and more recently Chen Cohen extend this interest into personal rituals that are performed in front of the camera and that take on an existentialist dimension, one that traces in the image a potential for memorialization at the same time as it reminds us of our temporal state.

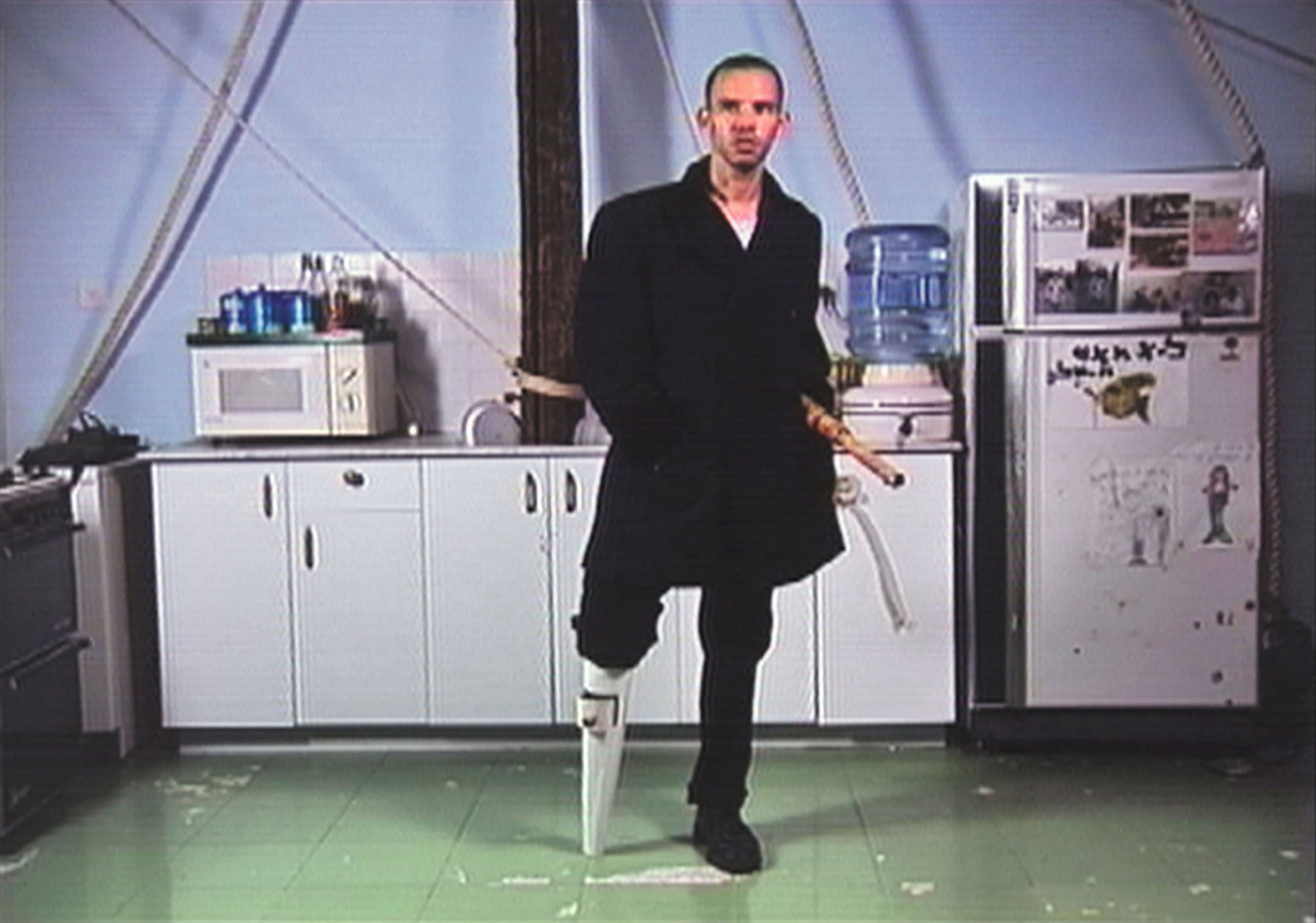

Other artists enlist the camera in a quest to highlight the absurdity of everyday life, and to infuse the mundane with a sense of the epic or of the fantastical. That is the case with Guy Ben Ner’s films, which largely take place at home, with himself and his immediate family as the actors; and with Ben Hagari who himself is the protagonist in an estranged, domestic world. Other artists, chief among them Tamy Ben Tor, use self documentation and irreverent role playing to examine the contradicting selves that we keep at bay and how we change according to social happenstance.

For artists like Rona Yefman and Tali Keren, the performative act and its documentation, taking place in the public square — be it in the separation wall in the West Bank or in Jerusalem’s city council — becomes a tool for political dissent. In recent years, the performing body and one’s unique body language have taken an added dimension in advanced image technologies such as motion capture, as seen in the work of Ruth Patir. As these examples show, the presence of the body and the record of a live action ground the work of art in reality, at the same time as the constructed image opens up to possibilities both of a personal and a political imagination.